Currency warfare is a way to export deflation

When a country depreciates its currency, its major trading partners depreciate their own currencies. They do this to save their economies from entering into deflation.

March 9 2015, Updated 6:05 p.m. ET

Why countries need to export deflation

When one country weakens its exchange rate, another country’s exchange rate gets stronger. This makes imports cheaper for the country with the strengthening currency. A flood of cheap imports in its markets hampers inflation. Inflation is boosted by increasing domestic demand. The increasing domestic demand is backed by price competitiveness.

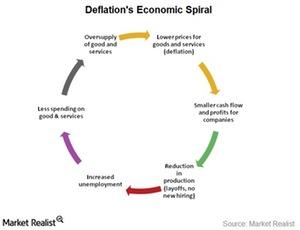

Now, the availability of cheap imports is detrimental to domestic producers. The producers are forced to reduce their prices in order to maintain their market share. Lower prices weigh down inflation. A persistent reduction in the general price level, also known as “deflation,” creeps into the economy.

As you can see in the above graph, deflation’s economic spiral is the main reason why exporting deflation is desirable for any economy.

As a result, when one country depreciates its currency, its major trading partners also follow suit to depreciate their own currencies. They do this to save their economy from entering into a deflationary phase. In a way, they export the deflation back to where it came from.

Currency warfare is a way to export deflation

Deflation is a consequence of and contributor to the global economic slowdown.

For instance, it has been leading the Eurozone (EZU) (VGK) closer to a recession. At the same time, it has been reducing demand for exports from countries like China (FXI). China is one of its major trading partners. Bilateral trade between the two regions grew tremendously over the years. China and Europe now trade well over 1 billion euros a day. European clothing and footwear firms—like Louis Vuitton and Chanel—compete with US fashion brands—like Coach (COH), Michael Kors (KORS), and Kate Spade (KATE)—for market share in the Chinese markets.

However, why would China suffer at the expense of a depreciating euro? It depreciates its own currency as well. Since the Eurozone is also a major trading partner to China—we discussed the bilateral trade in Part 2—the effect will be muted. Essentially, currency depreciation in both the trading economies will have no net effect on boosting growth in either of the economies. It’s plain currency warfare. It isn’t solving the problem of slow growth.

Over the last few months, many countries actively entered the ongoing currency war to fight the low growth deflationary environment prevailing around the world. The countries are using different means.

In the next part of this series, we’ll discuss the ways that a central bank usually attempts to make its currency cheaper compared to other currencies.