Broke Banks

“Banks are there to support businesses that have justifiable needs.” – Vijay Mallya, Indian businessman and politician, 2015 If corporate India is to thrive, it needs a healthy, functioning banking system. Socially useful projects and initiatives require capital and banks should be able to allocate this capital efficiently. While progress is being made, India’s banks […]

Nov. 20 2020, Updated 11:12 a.m. ET

“Banks are there to support businesses that have justifiable needs.” – Vijay Mallya, Indian businessman and politician, 2015

If corporate India is to thrive, it needs a healthy, functioning banking system. Socially useful projects and initiatives require capital and banks should be able to allocate this capital efficiently. While progress is being made, India’s banks still remain a weak point in the system.

The origins of India’s current banking problems lie in the corporate investment binge of 2003-2008, which resulted in overcapacity and overextended balance sheets. State banks, in particular, were instrumental, lending excessively to infrastructure and steel companies for unprofitable road projects, power stations and factories. These companies have now been left with high levels of bad and doubtful loans. Across the board, private investment is weak and companies are reluctant to spend, in some cases due to high levels of leverage. Banks, in turn, have been left with a high proportion of non-performing loans (NPLs) – those on which the borrower is not making interest payments or repaying any principal. They are not lending enough as a result.

However, there is significant differentiation across the banks, with stateowned banks suffering from NPLs of 10% or more, while private banks and finance companies have fared better with NPLs of only 1%. Appreciating the negative impact this could have on investment and future growth, the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) – India’s central bank – has

now urged lenders to clean up all bad loans by March 2017. The divergent fortunes of India’s banks became clear to us on our latest visit. On entering one public bank building, we waited in a sweltering, dilapidated room before meeting executives who, unlike the room, were quite cold. At another we were guided promptly to a pleasant, airconditioned room, complete with tasty refreshments and introduced to friendly staff who were excited to tell us about their business.

Encouragingly, things have improved somewhat in recent months. A collapse in input prices with minor changes in output prices has resulted in improved margins. There are initial signs that capital investment is starting to pick up, notably capital goods production and commercial vehicles sales. Nevertheless, in aggregate the sector remains subdued.

Rather than focusing on generating new business, one large lending company has been trying to improve its existing business and turn around underperforming accounts. In the mid-corporate sector, excess capacity in industries such as cement and steel has been – and still is – a problem. With the private sector unwilling or unable to participate in the current round of investment, pressure is on the government to bear the burden. All this is happening, with planned government expenditure having risen significantly this fiscal year. This will in part be helped by lower government spending on oil subsidies, which fell by 63% over the same period year-on-year. There is also scope for savings of around INR150 billion from the INR300 billion the government budgeted for oil subsidies if oil prices stay relatively stable.

From our field research, we have heard that the problem with a lot of lending is that the projects they are tied to have simply become unviable. This means that while recapitalization of the banks is needed, the SOEs could do a lot of it themselves by, among other things, selling off some of the huge amounts of real estate that they own. At present, there is no unified law that addresses corporate insolvency and bankruptcy. Instead, they are captured under a litany of numerous outdated Acts under the overlapping jurisdictions of four different institutions – the high courts, the Company Law Board, the Board for Industrial and Financial Reconstruction (BIFR) and the Debt Recovery Tribunals (DRTs). This has resulted in an overly complex process for resolving issues.

The passing of the Bankruptcy Code could be critical to revitalizing the banks. While the RBI has already allowed banks to take over defaulting companies, the new Bankruptcy Law will provide lenders with even greater security and speed up the process for dealing with bad debt. If these loans were addressed, the banks would be able to provide stronger support to the economy.

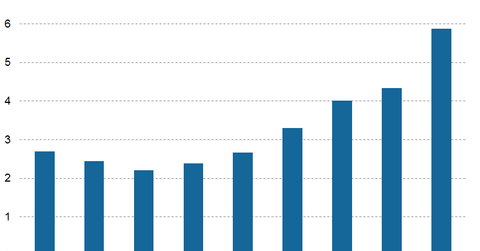

Market Realist – Non performing loans are a serious concern for Indian (EPI) (INDA) banks. According to the Reserve Bank of India’s semi annual financial stability report published in June 2016, the overall non-performing asset ratio for Indian (PIN) (IFN) banks is set to rise to 8.5% cent in March 2017 from 7.6%, under a “baseline scenario” (Source: Financial Times). The report also states that the ratio for state banks could go up to 10.1%.

The previous graph shows the bank non-performing loans as a per cent of total gross loans for India (INDY) (INP) over the past few years. The non-performing loans are set firmly on an upward trajectory, which could paint a grim picture for the Indian banking sector if not rectified in the near future.