What Should Be The “Right Amount” of Cash Allocation?

If you’re preparing your portfolio for the short term, the allocation to cash should be high. As the horizon increases, allocation to cash should go down.

Nov. 20 2020, Updated 2:51 p.m. ET

No “right amount” of cash allocation

While there is no such thing as “right amount” of cash allocation or allocation to any other asset class, investors need to consider both their return objectives and risk tolerance when making allocation decisions that are right for them. For a portfolio with a multi-decade horizon and high return objectives, cash positions could be relatively small; cash has been adding little to expected returns and investors should be able to manage the volatility with a long investment horizon. The shorter the time horizon, the more cash you should consider holding. Barring a very short horizon—say two years or less—a 30%–40% cash position would likely result in a negative after-inflation return.

On the other hand, a large temporary cash position makes sense for market timers, who believe they have the skills to move in and out of asset classes and profit from such actions. But as the State Street numbers suggest, for many investors it is easier to get out of the market than to get back in.

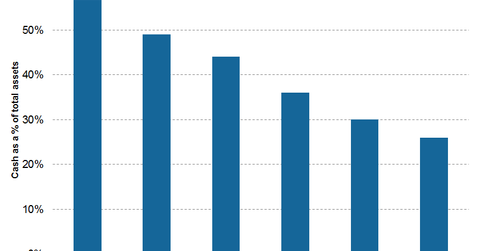

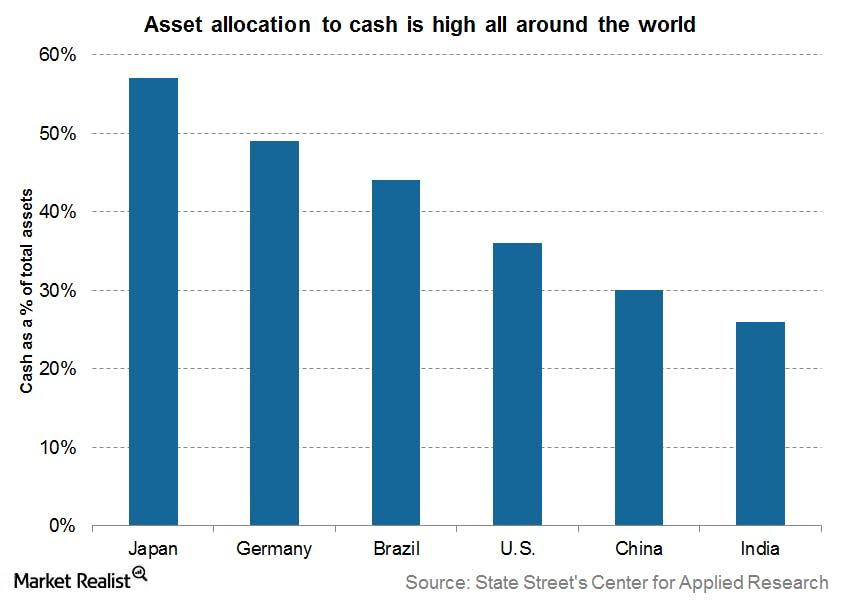

Market Realist – According to the 2014 survey conducted by the State Street Center for Applied Research, the global average asset allocation to cash was 40% among retail investors with investable assets. The global average rose from 31% in 2012 to 40% in the short span of two years, despite the strong bull run in the global and US equity markets (SPY). Allocations to cash by US investors shot up to 36% in 2014 from 26% in 2012.

The two crashes—the tech bubble burst of 2000 (XLK) and the US financial crisis (XLF) of 2008—are seared in the memories of investors, preventing them from moving out of cash into the markets. According to the survey, global retail investors save 22% of their incomes, 44% of which is invested in cash. The previous graph shows the average monthly allocation of investors to various assets.

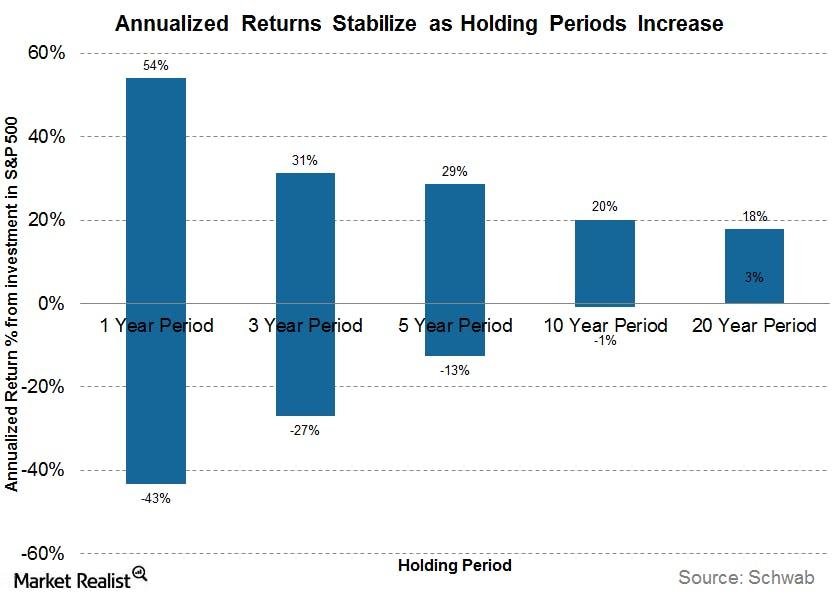

There is no “right amount” of cash allocation, however, for long-term portfolios, it is not advisable to carry a bloated cash position. The volatility of returns for equities reduces over longer time horizons. The chart above shows the highest, lowest, and average annual return of the S&P 500 over various holding periods (from 1926–2014). The longer the holding period, the lower the volatility (VXX) of returns. Hence, it makes sense to invest in equities (IVV), which give a better rate of return than cash, which depreciates with time.

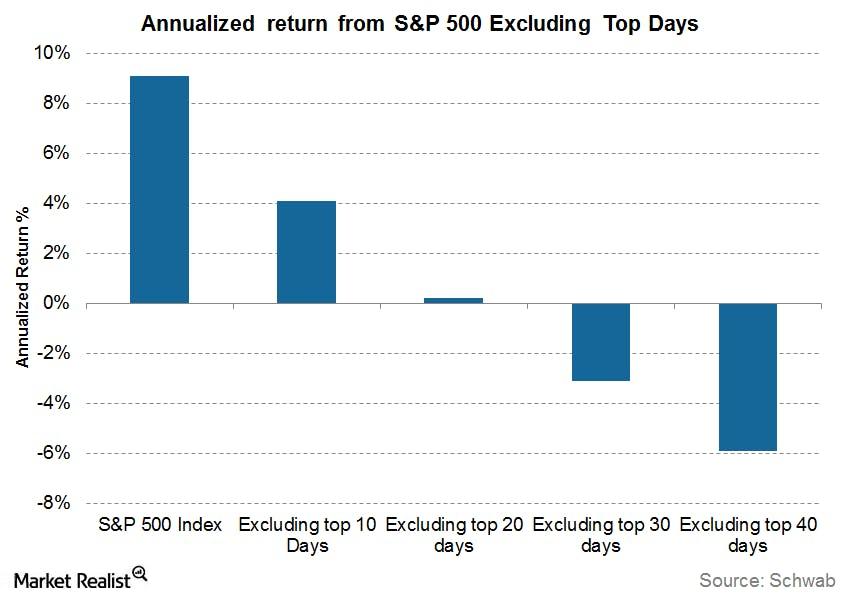

Not only does the value of cash erode with inflation, but you might not be able to capitalize on any opportunities that the equity and bond markets (TLT) (IEF) might present in the future. Missing out on top positive days of markets might drastically reduce your returns. The previous graph shows how your returns might be significantly lower than returns from the S&P 500 if you are not able to capitalize on the top days of the index.

So, if you are preparing your portfolio for the short term, the allocation to cash should be high. As the time horizon increases, allocation to cash should go down too. Be sure to diversify your equity portfolios with bonds, gold (GLD) (IAU), and other alternate assets to reduce volatility.

Read our series on How You Can Overcome 3 Bad Investing Habits to understand how you can maximize your returns by eliminating investor biases.