A Closer Look at Honeywell Aerospace’s Business Model

Honeywell has an installed base of 6,000 integrated cockpits, which is ten times greater than the next competitor.

March 15 2016, Published 12:31 a.m. ET

Business model: Why aftermarkets are no longer an afterthought

Honeywell’s (HON) original equipment, such as jet engines, last well over 20 years. In mature industries such as the aerospace (PPA) sector, there are limitations to the number of units a company can sell every year.

So, does the long repurchasing cycle effectively make this a low-growth business for Honeywell? Not really. These components are highly susceptible to wear and tear and require regular maintenance due to the mission-critical nature of their operation.

With this in mind, most aerospace customers also sign a long-term annual service contract with the same equipment maker they bought the equipment from, creating a highly profitable short-term sales component. How large could this revenue component be? Honeywell has sold so many units over the years that its commercial aftermarket sales were a full 12% higher than sales from the original equipment business. It all depends on the installed base. The larger the installed base, the larger is the aftermarket revenue.

It is a common industry practice to bid aggressively for wins, even to the point of selling engines below cost. After securing the contract, companies profit from the stream of lucrative service revenues over the life of the engine.

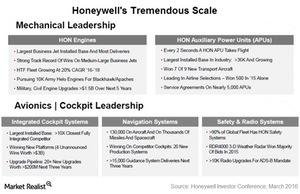

Honeywell’s tremendous scale

Honeywell has an installed base of 6,000 integrated cockpits, which is ten times greater than the next competitor. Similarly, with more than 12,000 jet engines and 36,000 auxiliary power units, it has the largest installed base in these product lines in the industry. Approximately 10,000 aircraft are under the Honeywell service agreement.

Business model of Honeywell Aerospace: Power by the Hour

Power by the Hour is a type of contract initiated in the 1980s by Rolls-Royce (RYCEY) and General Electric (GE), in which commercial airlines pay an hourly fee for using Honeywell’s engines instead of owning them. Therefore, Honeywell would lease the engine on a fixed-cost basis while retaining its ownership and the obligation to undertake repair work on its own dime.

These contracts enable airliners (XTN) to forecast and plan their expenditures with greater accuracy while eliminating the cost and risk of owning the equipment. Power-by-the-hour contracts are generally preferred when maintenance costs are uncertain. The US Department of Defense generally opts for fixed-price service contracts in which a fixed fee is paid annually when maintenance costs are more predictable.