Primer on mortgage backed securities, Part 5

Continued from Primer on mortgage backed securities, Part 4. Prepayment risk Prepayment risk and interest rate risk go hand-in-hand. The main difference between a mortgage backed security and a government bond is that with a government bond, you know exactly when you will get your principal and interest payments. If you purchase a 7-year Treasury […]

Nov. 20 2020, Updated 12:41 p.m. ET

Continued from Primer on mortgage backed securities, Part 4.

Prepayment risk

Prepayment risk and interest rate risk go hand-in-hand. The main difference between a mortgage backed security and a government bond is that with a government bond, you know exactly when you will get your principal and interest payments. If you purchase a 7-year Treasury bond, you know that every six months, you will get a 3.5% coupon payment and at maturity you will get your final interest payment and your principal back. If interest rates fall, the government cannot prepay your bond. You will still get your principal and interest back when you expect it.

With a mortgage backed security, there is a wrinkle. The borrower can prepay their mortgage without penalty. When interest rates fall, borrowers can refinance their home with a lower rate mortgage. To the MBS holder, this means that the principal they expected to receive over the life of the MBS (nominally 30 years) will be accelerated, and once it is paid out, the interest payments going forward will be smaller. To an investor, this means that they have to re-invest these funds into lower-yielding securities.

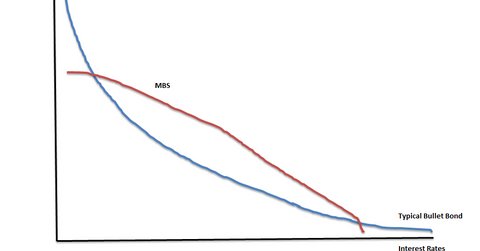

This illustrates a second risk to mortgage-backed securities, which is negative convexity. Duration measures interest rate risk – in other words, how does the bond’s price change as interest rates change? Convexity describes how duration changes as interest rates change. The longer the duration, the more sensitive the bond is to interest rate risk. The 1-year Treasury bill is relatively insensitive to interest rates compared to the 30-year bond.

With mortgages, you don’t know what the duration is because borrowers can prepay. So when interest rates fall, the expected life of the mortgage-backed security falls because more borrowers will prepay. This limits the price gains that MBS experience when rates fall. Conversely, when rates rise, MBS fall in price as does any bond. But, it also means that prepayments will fall, which will act to lengthen the maturity (duration) of the bond. And as we saw above, as duration increases, interest rate sensitivity increases. So, when rates fall, MBS don’t benefit much. But when rates rise, they get clobbered. This is negative convexity and it explains why a Ginnie Mae MBS with an expected life of 7 years yields 110 basis points more than the corresponding Treasury. You can see this illustrated in the chart above. When interest rates are falling, the price of a typical bullet bond increase faster than the MBS. Conversely, when rates increase, the MBS falls faster than the typical bullet bond. And when rates are stable, the mortgage backed security outperforms the bullet bond.

Back to Part 1.