The Federal Reserve versus Moore’s Law

Globalization, China, slow growth, and “transitory factors” such as cheaper cell phone plans help explain stubbornly low inflation. But they’re not the whole story.

Nov. 20 2020, Updated 11:18 a.m. ET

The U.S. unemployment rate is a low 4.3% and headed lower. Yet inflation remains below 2%. Globalization, China, slow growth, and “transitory factors” such as cheaper cell phone plans help explain stubbornly low inflation. But they’re not the whole story.

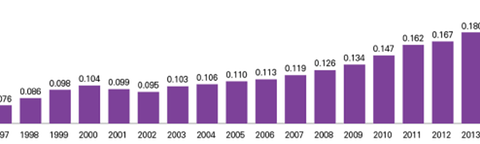

Technology is another important—and often overlooked—challenge that central banks face in sustainably meeting their inflation targets. Our calculations reveal that technology’s use in producing U.S. GDP is increasing exponentially. And technology’s reach extends well beyond Silicon Valley. In 1997, U.S. workers used $0.08 of technology to make $1 of real GDP. Today we use $0.20, and that number is rising. Increasingly, the Federal Reserve is going toe to toe with Moore’s Law.

Moore’s Law: A drag on inflation

Coined by Intel cofounder Gordon Moore, Moore’s Law has become shorthand for the diffusion of ever more powerful and cheaper technologies. We see it in consumer electronics—the smartphone that is twice as powerful and half as expensive as the one you replace, or the new TV that is flatter, sharper, and cheaper than last year’s model. These well-known, direct effects drag down measures of inflation for those products.

But Moore’s Law is about more than smartphones, TVs, and Amazon Prime. Its knock-on effects restrain the need for higher prices in every corner of the economy, not just in high-tech products. Prices are a markup over marginal costs, and in an increasingly digitized world, that marginal cost inches closer to zero. That’s the story told by our analysis of detailed industry data from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics and the U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis.

The growing reach of Moore’s Law

Note: Data cover January 1997 through December 2015.

Sources: Vanguard calculations, based on U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis input-output tables and data from Thomson Reuters Datastream.

To quantify how the increased utilization of technology is making it harder today to achieve 2% inflation, we identify the technology inputs used by each industry, from recreation and food services to law firms and utilities. We then compare the actual change in prices charged by each industry’s products and services (its Producer Price Index) with the change in a hypothetical index that excludes computer-based technology inputs.

The difference is striking. Since 2001, the declining prices of computer and electronic products, computer design and services, and other technology inputs have trimmed 0.5 percentage point per year from the prices that companies need to actually charge. If Moore’s Law didn’t exist, in other words, annualized inflation would have been 0.5 percentage point higher. Without Moore’s Law, core personal consumption expenditure (PCE) inflation would already be at 2%, and the Fed’s inflation target would have been achieved years ago. Interest rates would be higher.

Impact on industry

The impact has been most pronounced in technology-intensive industries, such as professional services and manufacturing. Moore’s Law helps explain how investment managers can now help clients diversify across global stock and bond markets at ever-lower expense ratios. It’s key to the longer-range, lower-cost electric cars rolling off assembly lines in Silicon Valley and Detroit. And it helps explain the slowing rates of inflation in the service fields of education, financial services, and retailing.

The low-inflation debate

There’s little sign that Moore’s Law has seriously entered the Fed’s debate about why its “medium-term” 2% inflation target keeps receding further into the future. Moore’s Law deserves a seat at the table in the low-inflation debate. It provides a more complete and accurate picture of the forces that will shape monetary policy and inflation expectations in the years ahead. And it bolsters our long-held view that tighter labor markets are less likely to set off the kind of inflation rates that they did before Moore’s Law was in full effect.

We live in a digital world that makes 2% inflation harder to achieve. The longer that inflation fails to reach its target, the more some will question whether such a target is ever attainable. The answer is a resounding “yes,” of course, for the Fed and any other credible central bank resolved to achieve 2% inflation. But to ensure a more convincing victory in their fight for 2% inflation, policymakers need to better appreciate this new technological challenger in the ring.

Joe Davis

Joseph H. Davis, Ph.D., is a principal and Vanguard’s global chief economist. He is also global head of Vanguard Investment Strategy Group, whose investment research and client-facing team conducts research on portfolio construction, develops the firm’s economic and market outlook, and helps oversee the firm’s asset allocation strategies for both institutional and individual investors. In addition, Mr. Davis is a member of the senior portfolio management team for Vanguard Fixed Income Group. Mr. Davis frequently presents at various investment forums and has published studies on a variety of macroeconomic and investment topics in leading academic journals. Mr. Davis earned a Ph.D. in economics at Duke University.

For more information about Vanguard funds or Vanguard ETFs, visit advisors.vanguard.com or call 800-997-2798 to obtain a prospectus or, if available, a summary prospectus. Investment objectives, risks, charges, expenses, and other important information are contained in the prospectus; read and consider it carefully before investing.

Vanguard ETF Shares are not redeemable with the issuing Fund other than in very large aggregations worth millions of dollars. Instead, investors must buy and sell Vanguard ETF Shares in the secondary market and hold those shares in a brokerage account. In doing so, the investor may incur brokerage commissions and may pay more than net asset value when buying and receive less than net asset value when selling.

Investments in bonds are subject to interest rate, credit, and inflation risk.

Diversification does not ensure a profit or protect against a loss.

Investments in stocks or bonds issued by non-U.S. companies are subject to risks including country/regional risk and currency risk. These risks are especially high in emerging markets.

All investing is subject to risk, including possible loss of principal. Vanguard Marketing Corporation, Distributor of the Vanguard Funds.