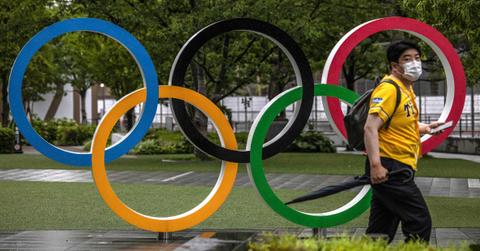

How the Olympics Can Leave Host Cities With Billion-Dollar Debts

How is the Olympics funded? The IOC chips in some money, and the host city pays for other expenses, but the preparations often go way over-budget.

July 19 2021, Published 4:01 p.m. ET

The Tokyo Olympics will finally kick off on July 23—a year behind schedule. As the COVID-19 pandemic took hold in March 2020, Tokyo’s Olympic organizers delayed the Games until 2021. Then, they squabbled with the IOC (International Olympic Committee) about who would fund the Olympics’ postponement, as the Associated Press reported at the time.

But the cost of the Olympics has long been a sore spot, especially because all of the Games since 2000 have gone over budget, sometimes by fivefold amounts, as Council on Foreign Relations data shows. The 2014 Sochi games, for example, cost more than $51 billion USD, blowing past the $10.3 billion initially budgeted. Six years earlier, the Beijing games coast $45 billion instead of the budgeted $20 billion.

Two distinct budgets finance the Games, including one from the Organising Committee for the Olympic Games.

In an explainer on the Olympics.com website, the IOC explains that the “basic principles of financing the Games … can be broken down into two distinct budgets,” the Organising Committee for the Olympic Games (OCOG) Budget and the Non-OCOG Budget.

The OCOG Budget comes primarily from the IOC, which earns money from The Olympic Partner program, the sale of broadcast rights for the Olympics, and other revenue sources. (The broadcast revenue has skyrocketed over the years, going from $1.3 billion in 2000 to $2.6 billion 12 years later, according to CFR data.)

The IOC also “provides the possibility to the Games organizers to commercialize the Olympic rights in their territory as well as to manage the ticketing of the event,” the committee adds.

Meanwhile, the Non-OCOG Budget covers capital investments and operational services.

The Non-OCOG Budget is controlled by local authorities, according to the IOC. This budget includes a capital investment budget for the construction of competition and non-competition venues; and an operations budget for security, transport, medical services, customs and immigration, and other operational services.

“In addition, each city/region/country has a long-term investment plan for general infrastructure which deals with wider infrastructure investments that the host country and city are making independently of the Games, such as investments in roads, airports, and railways,” the committee adds. “How this is funded and the scope of this investment plan very much depend on what already exists in the city and the long term development vision of the city and country.”

However, these investments can take years or decades to pay off. The CFR reports that it took nearly 30 years for Montreal taxpayers to pay off the city’s $1.5 billion debt from 1976 Summer Olympics in Montreal. Researchers found that the 2014 Winter Olympics in Sochi will cost Russia $1.2 billion per year.

Not surprisingly, some prospective host cities have taken their names out of contention for future Olympic Games. Oslo and Stockholm gave up on hosting the 2022 Games after considering the budgetary impact. Boston backed out of consideration for the 2024 Games. The mayor of Boston said that he “refuse[d] to mortgage the future of the city away.”